I remember it well. Sitting down in the classroom at Bard CEP on a crisp morning in the Winter of 2013 to a class that I found both enlightening yet simultaneously intimidating, Environmental Economics. It was the first lecture of the semester, and we were set to discuss Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES). While I was familiar with the concept of ecosystem services, I was largely unfamiliar with the PES tool except for a brief mention of the tool in an international environmental policy course I took as an undergraduate. In order to prepare for class, we were required to read Stefanie Engel, Stefano Pagiola, and Sven Wunder’s “Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues”. After studying PES in environmental economics, and in our science and policy courses, I remember walking away with what I thought was a solid understanding of a conservation tool that used financial or other incentives to encourage landowners to protect ecosystem services. What I didn’t understand at that time was just how complicated the PES scheme could be when applied in the real world.

Fast-forward four months to June 2013 and I’m sitting with my internship supervisor John Schwartz discussing my assignments for that summer. As I reported in my first blog post this summer, my work with the New York City DEP’s Watershed Protection Program (WPP) directorate in the Working Lands section in their upstate faction of the Bureau of Water Supply encompassed a variety of different tasks. While I spent time analyzing data and creating a report on the WPP’s watershed forestry program, I also conducted fieldwork with a colleague collecting data on plant growth/survivability for a number of watershed landowners participating in the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, also known as CREP. The CREP program is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), with DEP providing matching funds. This program provides watershed farmers with incentives to exclude livestock from nearby waterways, establish riparian buffer zones, and to remove pasture and crop lands from production. Over 2,000 acres of buffers have been established over the past 16 years, and more than 11,000 head of livestock have been excluded from streams. In this capacity, I monitored and evaluated the success of CREP planting by taking field measurements of trees and shrubs and developing a database to support multi-year monitoring efforts.

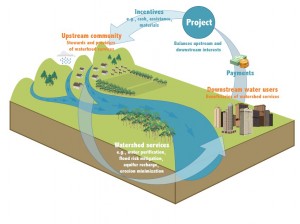

In addition to the aforementioned work, I delved into a research project that was of academic and professional interest to John and DEP. Continuing what a previous summer intern had uncovered in the years prior, I began to conduct an in-depth literature review of PES models. As I began my research, I was interested to find that a subset of PES, known as Payment for Watershed Services or PWS had emerged. PES and PWS work to protect vital ecosystem/watershed services through the exchange of monetary incentives for the adoption of specific land management practices. What really stuck out to me throughout my research was the number of times New York City was mentioned as a prime example of a PES model in action. Nearly every academic paper I came across cited the New York City watershed, and programs implemented to protect the city’s water quality such as the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, as the pinnacle of a PES program in practice. Despite what I was reading in the papers, in speaking with DEP employees about PES and its presence in the NYC watershed, it was made clear that New York City did not design its watershed protection programs under the guise of the PES framework. This paradox between what academic papers were saying about New York City, and how the DEP–the city agency responsible for managing and implementing NYC’s watershed protection agenda–perceived its watershed protection programs sparked my interest in further examining the presence of the model in New York City.

What began as a summer research project morphed into a master’s thesis proposal. For my thesis I decided to examine the extent to which PES is being implemented in NYC’s watershed protection programs. In addition to conducting a review of literature on the PES model, my thesis will incorporate qualitative data collected from interviews conducted with DEP employees to analyze the extent to which NYC’s watershed protection programs are implementing the PES schematic. The interview questions are based on a set of six criteria used to define PES that were established throughout the literature. I will also use quantitative data collected this summer as part of my fieldwork in evaluating the survivability of plants planted through the CREP initiative in the watershed. This portion of my thesis will serve as an in-depth look at one of NYC’s watershed protection programs used to maintain water quality for its customers. The results of this chapter will provide a comprehensive picture of how one of the watershed protection programs most often cited as a PES framework in practice in the literature is cohesive with the model, and also how effective it is in achieving the conservation objectives set out in NYC’s groundbreaking Memorandum of Agreement document—which stipulated the regulatory and institutional framework required to implement its water supply programs.

My first year coursework at Bard CEP greatly prepared me to intern with DEP this summer. Despite growing up in New York City, it was not until I was introduced to the complexities of the DEP’s work that I understood just how large of an undertaking it is to maintain NYC’s high water quality standards and to provide the city’s 8 million residents with fresh drinking water. Events such as a tour of a watershed farm accompanied by a Watershed Agricultural Council representative during orientation, classes focused on the history of the NYC watershed and its Filtration Avoidance Determination, and a fascinating presentation from John Schwartz (who would eventually become my intern supervisor at DEP) piqued my interest in the watershed and DEP’s work, and prompted me to pursue an internship with DEP this past summer. Furthermore, the introduction to the PES model in my economics, science, and policy courses helped me grapple with how governmental officials and policymakers, upstate watershed residents, and NYC citizens all interact with the framework in different ways. This understanding has shaped my approach in analyzing the model and its role in the NYC watershed in my thesis. I am grateful both to Bard CEP for stoking my interest in watershed policy and protection, and to DEP and my supervisor John Schwartz for giving me the opportunity to intern with the Working Lands section this past summer.