Bard MBA News

At Work – When Women Prefer Gents

By Bard MBAWritten by Kerry Sinclair, BardMBA ’15 originally published via LinkedIN

Recently, I was surprised to learn of findings from a 2014 Gallup report, concluding that women still prefer to work for men. Rebecca Riffkin said “Women are more likely than men to prefer a female boss” – that 33% of women who would rather have a male boss and only 20% of women favor working with other women.

But how true is that really? Harvard Business Review conducted a survey to see if these assumptions were factual, and found that “likability and success actually go together remarkably well for women” – proving that women leaders are actually perceived as slightly more likable than their male counterparts.

….46% of employees have no gender preference in leadership at all.

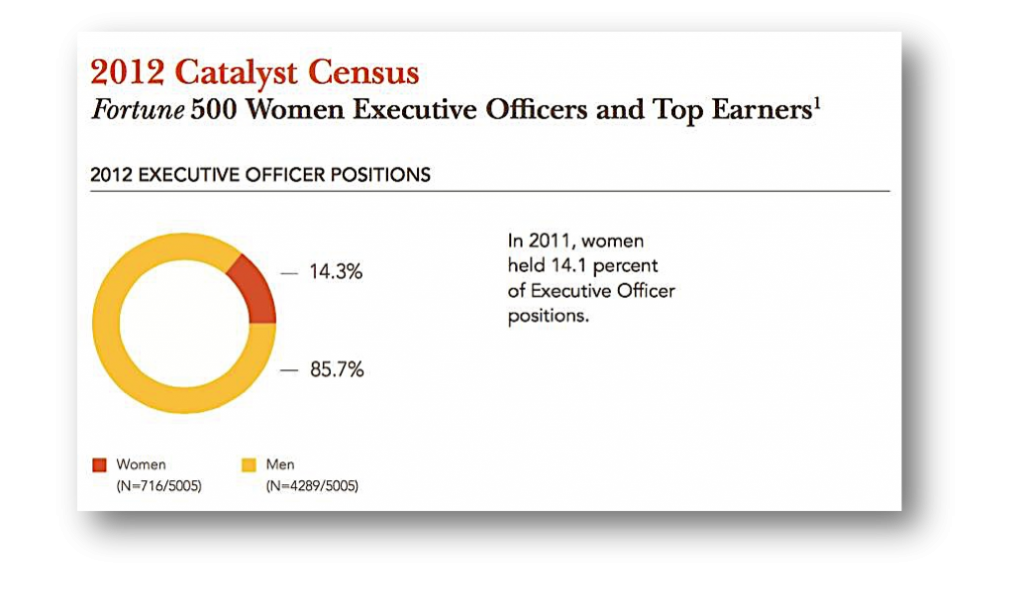

Data tells us that women are generally liked, and 46% of workers tell us that there is no gender preference for leadership – and yet a Catalyst study revealed only 14% of women hold top-level jobs in 2011. So what’s the hang-up?

It is naive to assume that organizations, and the individuals that create them, can subvert those foundational elements of human socialization

Many women can pinpoint a time during childhood where the expectations of gender began to form a worldview; it may have happened when some friends decided to play sports or take part in activities typically reserved “for boys”. Choosing to be a ‘guy’s girl’, as I did, challenged and perplexed our parents and their friends, but it also placed us outside of traditional peer groups. It is naive to assume that organizations, and the individuals that create them, can subvert those foundational elements of human socialization. A pivotal moment for a girl is when she realizes that pursuing her own interests may draw the suspicion of her peers and appear as a challenge to the community. That moment echoes through adulthood when a woman is positioned as an outlier professionally, by taking on roles that few other women have stepped into.

Around the world women are driving change and asserting influence through increased education, more active participation in government as well as in business. The Center for American Progress reported on late-stage development in the U.S:

- Women account for 60% of undergraduate and master’s degrees, including 47% of law and 48% of medical degrees

- More than 44% of master’s degrees in business and management, including 37% of MBAs

- Are 47% of the labor force and 59% of college-educated, entry-level workforce

“Occupational segregation and reduced working hours, … explain around 30 percent of the wage gap, on average” – IMF Report on Women & Macroeconomy

Power structures are still dangerously unequal, however:

- Women represent 20% of global political leadership

- Women spend on average 2.5 hours a week engaged in unpaid labor

- Tax disincentives: the tax wedge applied to secondary earners—often married women—will be higher than for a single but otherwise identical woman (IMF. 2013)

A well-known adage maintains that “behind every great man is a greater woman”, which is quaint at best and serves to diminish the direct impact women have at work while reinforcing patriarchal values, relegating women as support systems and subordinate to men. Girls may be encouraged to “think outside the box” and are taught that it is ok to be ambitious and innovative, but they are also cautioned not to be “bossy” or demanding so as not to disrupt the flow of status quo social architecture. And those who do will be forced to forfeit their femininity, in order to be “accepted” by members of the ‘Boy’s Club’. As a result, Matt Symonds of Forbes points out:

“Today, women occupy just 4% of CEO spots at Fortune 500 companies, and fewer than one in five corporate board seats is held by a woman”

This script has been handed to young women for centuries, and directly contributes to and may cause much of the violence and oppression against women. Effective leadership requires confidence in one’s self and the confidence of others who are willing to be led or guided. When a woman is told by both genders that she isn’t made of the stuff to lead, because women, as a class or category, do not have the skills, characteristics or intellect required to lead, she may second-guess herself. When insecurity replaces confidence as a driver, it can undermine even the most promising or capable leader. As anyone who has been an outlier might attest, navigating an unwelcome terrain while remaining legitimate requires adopting a protective veneer of sorts, i.e. an intimidating presence to thwart pushback – and for some women who are fighting to be heard or trusted for their counsel, it has proven an effective style for management and career development.

That style is no longer working, now that the critique is from both men and women. In the next few decades’ women will be facing increasing competition for top positions from other women. It’s important that the structural dynamics of organizations are designed to enable women as leaders and colleagues. And it’s also important for men to understand these dynamics, so they can help to create change.

Growing up men are taught to compete with other men, and often for the attention of women. Thus they acknowledge the inputs of men with more gravity than they acknowledge the input of women. They are taught to compete for power and prestige – and women are considered a reward for those who achieve that status. Alternatively, women are taught to compete with each other, not for power or influence, but rather for the attentions of the men with achieve a certain level of that status. Women are taught to attract a husband by being pretty enough, and also smart enough to secure him. And although antiquated as a perspective, it’s still very alive and relevant in our culture.

“She’s too pretty/smart, I could never be friends with her”

Women who take issue with working for other women – especially those who are “smart and beautiful” confer power to that stereotype. Saying, “She’s too pretty/smart, I could never be friends with her”, is a flippant statement common among women, when discussing other women. The ways in which patriarchy insidiously situates itself into the interior and collective lives of women are evidence of these beliefs i.e. that establishing friendships with women who are smarter or more beautiful will dampen ones chances to attract a man. Men are the ultimate “prize” and women are the “competition”.

The Defensive Offense

Social values get translated into workplace relationships. If women experience being in the company of a woman who is perceived as “superior” as a disadvantage, then it is less likely that they will want to take direction from her. And if the woman responsible for delegating tasks and executing projects feels insecure or under suspicion, she may necessarily adopt an “offense as defense” in order to deflect and pushback from her direct reports – male or female. Finally, while it’s true that some men may react strongly to taking orders from a woman, others may get off a bit easy in this dynamic relationship, as they haven’t yet been socialized to take seriously the tension between women. Just as the adjectives used to describe women are flippant or dismissive in nature i.e. “catty”, “bitchy”, “nervous”, or “too aggressive” – the attention that is given to woman-on-woman conflict is similarly treated by categorizing it as lacking weight, seriousness or merit (“that’s just how women act.”).

“Since women make up half the world, their role in achieving sustainability objectives cannot be over-emphasized” – PriceWaterhouseCooper

Because many women have been indoctrinated into that rhetoric, men have generally not been forced to step outside the box of the dominant culture. Although today’s workplace is still dominated by men and so reinforces patriarchal norms, women have become central drivers of productivity. As more men recognize the critical market insights and organizational capability that women bring to leadership, women will be less pressured to diminish their own value or be put at odds with each other whether as colleague, employee or director.

And personally? I just want to work with people who are committed to their team and to the mission, and who keep focus on gaining a competitive edge.

Posted on 25 February 2015 | 10:18 am