“Check out these masks that Kat’s mom made us. 2 for each of us <3”, I sent from New York, in a text message to my mom and brother.

“Found the n95 mask!” my brother, in Massachusetts, responded two days later.

These texts, sent after weeks of shopping in makeshift masks, illustrate the scarcity of safety supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Essential workers are experiencing shortages at work, and individuals are scrounging up safety gear at home or competing for quickly sold out, internationally made, personal protective equipment (PPE) from home improvement stores or pharmacies.

I want to offer an alternative paradigm, one that focuses on the role of strong local and regional supply chains in building resilient economies. Those resilient economies then better equip communities to respond to global phenomena like a pandemic or even climate change impacts.

How One Community’s Response to PPE Shortages Proves the Necessity of Shorter Supply Chains

My hometown, Worcester, Massachusetts is one of many communities leveraging local capabilities to address the shortages of masks and PPE. Within weeks of the first COVID-19 shutdowns, fast-acting localized supply chains facilitated by small business owners and newly organized networks, like Mutual Aid Worcester, Worcester Face Shield Project, Worcester Stitchers for Health, and others have responded to the shortages.

Multinational businesses located in the city and local manufacturers who previously produced goods for the global market have stepped up to join the networks of DIYers making PPE in their home and makerspace workshops. The successful actions taken by these local networks, from which even multinational and locally-owned manufacturers took their cue, are a testament to the necessity and resilience of local and regional supply chains.

If people-and-purpose-driven local supply chains are saving the day during the COVID-19 pandemic, while profit-driven global supply chains are failing to keep our communities safe or promote resilient economies—is there a case for local supply chains as a key strategy to address climate change?

A recent edition of McKinsey Quarterly explored the importance of localizing supply chains to alleviate pandemic risks as well as climate change risks.

Mitigating Climate Change Risks by Shortening Supply Chains

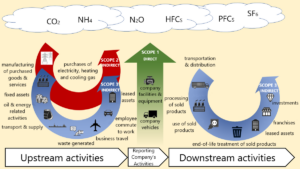

Specifically, shorter supply chains reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of a company’s value chain. A company’s value chain emissions include not only its own activities, but also activities that are upstream and downstream from it. The majority of these upstream and downstream activities generate Scope 3 emissions— vendor emissions in order to make and ship a part for a company’s product and emissions emitted by customers during and after product-use.

Scope 3 emissions represent the single largest source of emissions for the majority of sectors. However, they’re controlled by a company only to the extent that it can influence the behavior of its vendors and customers—which is difficult to do when those vendors and customers are thousands of miles away adhering to different standards and alienated from the implications of the product’s life cycle.

But what if a company’s vendors and customers were within 100 (local) or 500 (regional) miles of each other? Its sphere of influence increases and its Scope 3 emissions decrease.

Plus, lines of communication now travel omnidirectionally, driving solutions from all parts of the supply chain and resulting in full supply chain accountability. The ability of such a system to respond to the local realities generated by global phenomena is enhanced, as is observed in the case of Worcester’s response to mask scarcity due to COVID-19.

Sustaining these newly developed shortened supply chains post-COVID-19 will better prepare communities for the impacts of other global phenomena they will endure, and assuredly those correlated with climate change.

In the case of short-term impacts like damages from climate induced natural disasters, well developed short supply chains will be nimble enough to respond commensurately. With respect to long-term impacts like rising sea level in coastal regions and increased average annual temperatures, short supply chains will lessen their magnitude due to reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

How the Local Food Movement is Proving that Shortened Supply Chains Create Resilience

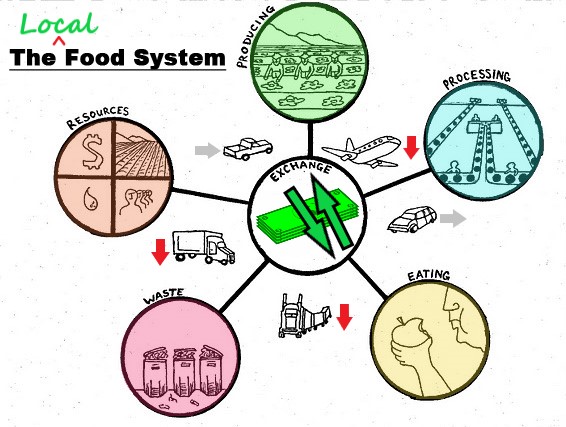

It’s for reasons like these that initiatives like Food Solutions New England’s ™50 by 60, a goal for the region to produce at least 50% of its food by 2060, are so critical.

Today, purchases at the local farmers market or through community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs illustrate ways in which people engage in hyper-local supply chains, thereby reducing the downstream Scope 3 emissions of local farms (e.g. customer emissions to get to and from the location of sale, the treatment of imminent waste, etc.). The upstream Scope 3 emissions of farms with an appetite for local and regional supply chains are also reduced given a decreased amount of manufacturing and transport of fertilizers, composts, and manures (among other inputs and supplies).

And according to the National Grocers Association, we are even engaging in relatively shortened supply chains in some grocery stores, particularly local and regional grocery stores where offerings of products from local suppliers are part of the value proposition.

While we know that local purchasing isn’t the most effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from our food, it does still make a difference, and what is remarkable is that “for every $100 spent at a farmer’s market, 62 percent stays in the local economy”.

The resulting local economic resilience from emissions-reducing shortened food supply chains is a critical co-benefit in the strategy for climate change mitigation.

Of course, drawbacks exist: local doesn’t always equal the cheapest option and adjustments must be made based on local and regional capacities (e.g. crop seasonality). One can argue that the former is due to the lack of economies of scale, but I would be remiss to leave out the fact that small local producers receive very little in the way of government food subsidies in comparison to multinational food conglomerates and the mega farms that produce for them. The latter can be solved by pragmatism: there may be times when lengthening the supply chain is necessary.

Undoubtedly though, the durability of shortened food supply chains will need to be supported by a paradigm shift in the food policy that drives subsidies. Additionally, it will need to be supported by a realignment in food companies’ priorities—profitability need not be the guiding light.

We’re seeing glimpses of this priority shift due to COVID-19 closing restaurants, food suppliers’ most profitable segment. As a result, food suppliers are developing more local and regional outlets in the grocery segment, where profit margins are smaller, but where they’re essential to keep business going and address urgent needs.

Similarly, strategies to mitigate climate change will be well served by including a shift to stronger local and regional supply chains that’s supported by adequate policy. Such a paradigm shift would amplify all participants’ accountability and experience of the impact of the supply chain, incentivizing social and environmental responsibility, and enabling agile responses to local impacts.

Re-imagining Our Supply Chains to Build Climate Resilient Communities

In 2017, Forbes contributor Jonathan Webb authored an article about building a local supply chain as a response to what he anticipated was a phase of protectionism requiring U.S. companies to reconsider their global supply chains. However, local supply chains built upon protectionist policies driven by fear and nationalism will not aid the goal of climate resilience.

While the solutions must be local and regional, the issue of climate change is a global one, and solving it requires global coordination and cooperation.

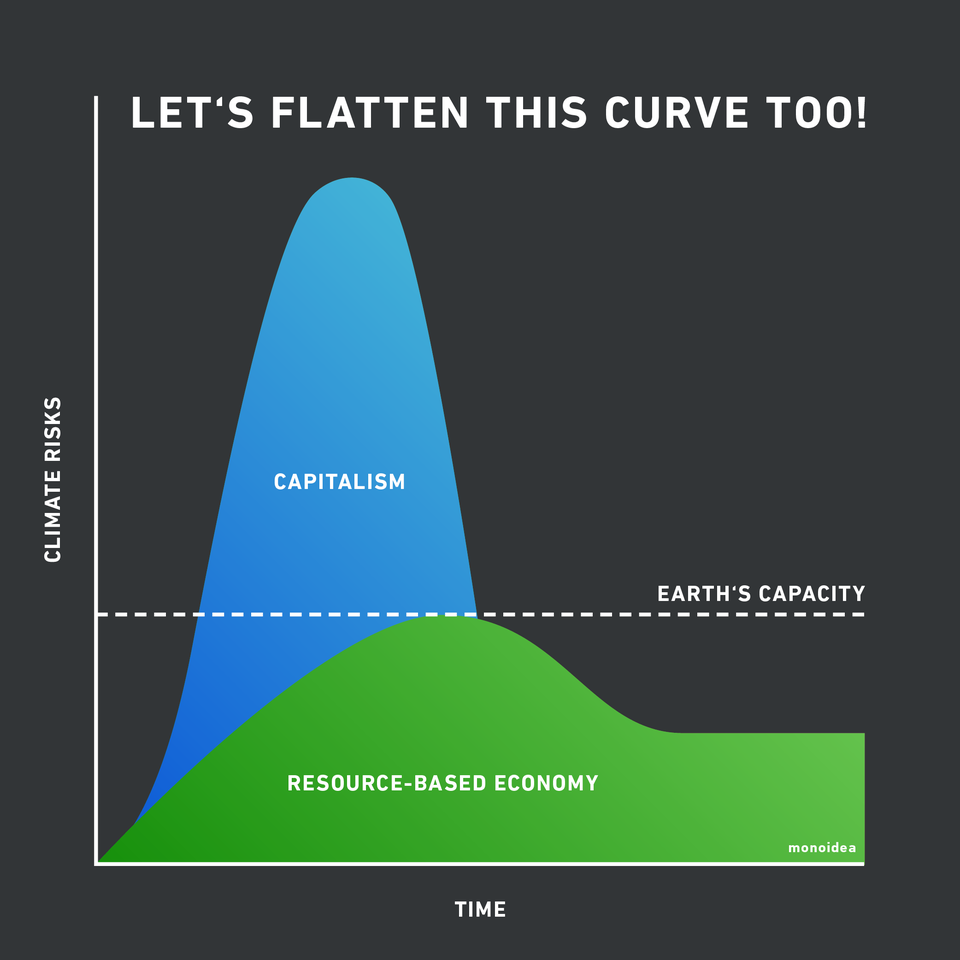

This is therefore not an indictment of globalism, but an indictment of capitalism in practice, which has utilized globalism to serve its sole aims: profit generation and wealth accumulation to no end and at all costs.

Instead, climate resilient communities will be supported by local supply chains built on a foundation of “commonomics” or “communalism” driven by democratic participation, a desire for living economies, and living within planetary boundaries. In the same way that we’ve been given tools to “flatten the curve” of COVID-19 transmissions, shortened supply chains are a tool that may help us to “flatten the curve” of our extraction of Earth’s resource capacity.