On November 15th, the Land Trust Alliance brought together leaders in land conservation across New England recognized for their outstanding performance. Twenty-five people from ten land trusts gathered at the Alnoba Lodge (Alnoba comes from an indigenous word for “Change”) for a day of high-level discussion and peer-to-peer learning as part of an ongoing discussion about community conservation.

The concept of community conservation has become an unofficial “theme song” of my internship; some piece of my work could always be traced back to it.

For those who aren’t familiar with the concept or haven’t read my previous blog post, community conservation is an approach to land conservation that represents the diversity of peoples and their needs in communities across the world. It is NOT a call for an anthro-centric (human-centric), utility-based approach to conservation, but rather asks the question, “who is not being served by conserved land and how do we make it accessible?” While we all benefit from conserved land in the clean air and water it collectively provides, those benefits are not always equitably shared or even perceived in each community.

So There I Was…

On that November day whose cold and rainy weather was emblematic of my post-election season mood, I was preparing to share my perspective on community conservation with a group of land trust board members. After a deep immersion into the subject throughout my time with the Alliance, I felt I was prepared to artfully interject into the breakout discussion with just a touch of insight that would spur conversation to an enlightening crescendo. That didn’t happen.

Instead, we mostly argued semantics over the questions we were meant to answer. Just as I was about to give into frustration, an interesting thing happened. From our deadlocked, chicken-or-the-egg conversation about conserving land for the biodiversity it held or the people who would ultimately steward it, I was transported back to my first year at the Bard Center for Environmental Policy. I was working on a literature review of a deeply theoretical body of work around Socio-Ecological Systems (SES). In a nutshell, an SES is community of individual people, governing systems, ecosystems, and species that interact and create outcomes.

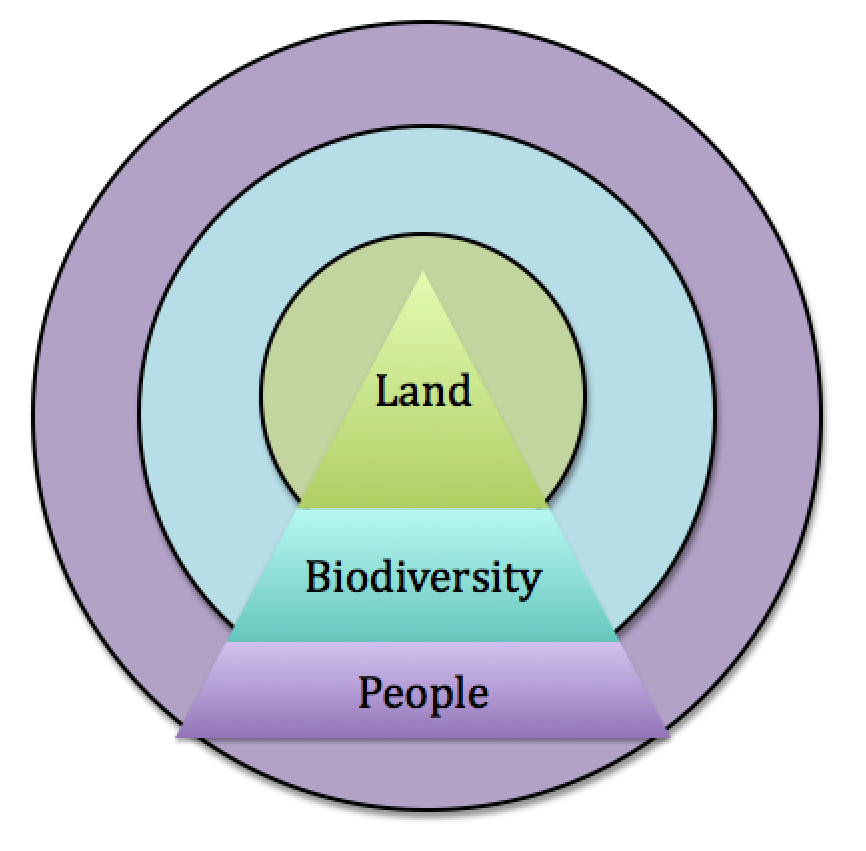

That’s when it occurred to me that my message to this group of land trust board members was all wrong. Land, biodiversity, and people do not stack up in a hierarchy as I had been trying to argue, but rather in concentric rings around a center, where each is supported by the layers inside.

I wager I might already know what you’re thinking. But Collin, couldn’t futuristic, space-dwelling humans be supported by a few of our favorite domesticated plants and animals? At a bare minimum to survive, yes. But this begs a much deeper question: is our quality of life determined by having what we need to survive or by the richness of the world around us? This question strikes at the heart of what renowned biologist and author E.O. Wilson meant when he said:

The human hammer having fallen, the sixth mass extinction has begun. This spasm of permanent loss is expected, if it is not abated, to reach the end-of-Mesozoic level by the end of the century. We will then enter what poets and scientists alike may choose to call the Eremozoic Era — The Age of Loneliness.

~ E.O.Wilson, “The Creation: An appeal to save life on Earth”, 2006.

It’s a very bleak and disheartening realization that we–the human species–may be so willing to continue on our present course of consumption, sacrificing so much of what makes life on this Earth so rich. But it’s also a position I think we can still work to come back from.

My Hope for the Future

Land that is protected, rich in biodiversity, and accessible to people from all walks of life is a powerful thing. To date, 56 million acres have been protected in the United States by state, local, and national land trusts, and over 6.25 million people visited that land in 2015 alone. The entirety of this conserved land offers the broader public much more than recreation.

- The Nature Conservancy estimates that halting deforestation, conserving land, and restoring ecosystems can achieve more than 30% of the targets set by the 2015 Paris Climate pact.

- Privately conserved land like that of land trusts creates legal protection for endangered species and biodiversity hotspots.

- Added time spent in nature has been shown to increase our well-being and kindness.

- Nature has a transformative ability on a person that connects us to our world and our communities. All over the land conservation world are stories of transformation, triumph and joy brought about by a connection with the land.

These facts illustrate a truth that humanity has long known and has recently come close to forgetting. In a sense, “Socio-Ecological Systems” and “Community Conservation” are just fancier terms for what Aldo Leopold dubbed a Land Ethic. It the belief that the living biosphere of the Earth is a community to which you and I and the other 9 billion people on this planet belong. And as Leopold himself said, when we begin to see ourselves as part of that community, we may begin to use it with love and respect.

All around us America is deeply polarized, cast onto one side or the other. How we treat the land cannot and should not be a polarizing issue. It is something we all depend on and is part of the solution to regaining common ground (pun intended). Land trusts know this. In fact, the IRS requires land trusts to remain non-partisan by law. As a result, land trusts have been enormously successful across the political spectrum.

Listen

Even in states in which environmental causes have been caught in a political crossfire, there is something to be learned from hearing (not just staring while they talk) what your ideological opponents have to say.

As our director here at Bard CEP, Eban Goodstein, often reminds us (as he did in a recent blog post): sustainability just makes sense. There are lessons to be learned from Right-leaning, oil producing states like Texas, the nation’s biggest producer of wind energy. Sustainability just makes sense. Perhaps surprisingly (or not), 75 percent of Trump voters support accelerating the adoption of renewable energy. Sustainability just makes sense!

I would like to share something I’ve learned with you. I’ll let you in on the biggest lesson to come out of my internship. Don’t blink or you might miss it. Ready?

Listen.

Listen to your neighbors, your coworkers, your friends, that relative of yours who gets a little too political around the holidays, the radio talk show host you were about to pass by, and especially listen to that person who you just can’t ever see eye-to-eye with. You may realize that your views, which we so liberally assign to party lines, are really not so different. And when it comes to our land, we cannot and should not allow it to become a partisan issue. It matters to all of us. Then after you’ve really listened to what others think, talk to them about climate change. Tell them why that’s important to you. Oh, and it might just keep you sane as well.

For more about the Land Trust Alliance and community conservation you can watch the following inspiring videos from Rally 2016 on YouTube.

GREAT JOB COLLIN!

Thank you, Kevin! I look forward to chatting with you more about YOUR internship this Spring!