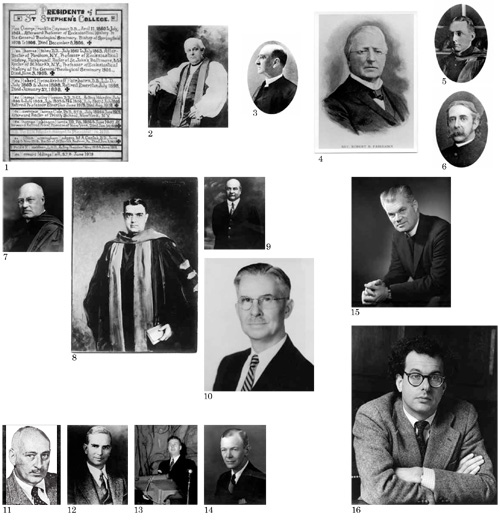

1. Presidents List, ca. 1919. This image

represents a framed, hand-inked list of the

presidents of St. Stephen’s College, along

with their degrees, dates of service, and

deaths where applicable. This was probably

completed soon after the arrival of Bernard

Iddings Bell in 1919.

2. George Franklin Seymour, 1860. Seymour was the first warden of St.

Stephen’s College. The title of warden

reflected its English use, to indicate a

college president. Rev. Seymour had, for

several years prior, served as missionary of

Annandale and had been tutoring students

in the classics to prepare them for entrance

into the General Theological Seminary.

These six students represented the core of

the first class of St. Stephen’s College. Rev.

Seymour presided over the College’s first

commencement in 1861, with two students

receiving degrees. Warden Seymour

resigned soon after, and eventually became

the Bishop of Springfield, Illinois.

3. Rev. Thomas Richey, ca. 1862. Rev.

Richey accepted the position of warden in

1861and remained for two years. Aspinwall

was built during his administration,

greatly expanding dormitory capacity for

potential students.

4. Robert Brinckerhoff Fairbairn, ca. 1870. Known as “The Great Warden,” Fairbairn

headed the College from 1863 until 1898.

Under his steady guidance, St. Stephen’s

grew into an institution recognized for its

academic rigor. The historic architectural

core of campus was also established during

his tenure, including the construction of

Ludlow-Willink (1866), the Stone Row

buildings Potter and McVickar (1885),

North and South Hoffman (1891), and the

Hoffman Library (1893). He died within two

weeks of John Bard in 1899, effectively ending

the “early years” of St. Stephen’s.

5. Rev. Lawrence T. Cole, ca. 1900. Rev.

Cole was not yet thirty when he accepted

the position of warden at St. Stephen’s in

1899. He introduced a modified elective

program, and abolished the traditional

“Preparatory Course,” for those students not

yet prepared for the advanced Latin and

Greek in the College’s curriculum. He left in

1903, but remained on good terms with

St. Stephen’s, returning years later to serve

as trustee.

6. Rev. Thomas Robinson Harris, ca. 1905. A veteran of the Civil War, Rev. Harris was

warden of the College from 1904 to 1907.

Though plagued by ill health, he brought

enrollment up by replacing the “Preparatory

Course” altogether. At his retirement, Rev.

George B. Hopson served as acting warden

at St. Stephen’s.

7. William C. Rodgers, ca. 1910. Appointed

in 1909, Rodgers brought new energy to

St. Stephen’s. Signaling the changes he

was to make, Rodgers changed his title to

president, (though B.I. Bell again carried

the title of warden for several years). Under

the Rodgers administration, the campus

was modernized: Electricity, a sewage

system, and central heating systems were all

installed. The Chapel was remodeled, and

Gerry House was built to house the president’s

family, as well as serve as a gathering

place for entertaining students, staff, faculty,

and guests. To make way for Gerry House,

it was necessary to move the observatory

down the hill, where the structure still

stands as the chaplain’s office. Dr. Rodgers

resigned in 1918.

8. Rev. Bernard Iddings Bell, ca. 1920. Rev.

Bell was the last administrator to carry

the title of warden. His vision and energy

permanently altered the physical and social

geography of the College. Under his tenure,

many buildings were constructed, science

was emphasized, a nationally renowned

athletics department was created, and

legions of students were deeply impacted

by his educational philosophy and personal

charisma. Under Dr. Bell, the College sought

to “give men four years of classical and cultural education as a background for life,

and as a basis for graduate specialization

or professional study.” It was through his

leadership, as the College faced one of its

many financial crises, that St. Stephen’s

merged with Columbia University in 1928.

Bell resigned in 1933 |

9. Nicholas Murray Butler, 1930. As president

of Columbia University, Butler was the

official president of St. Stephen’s, renamed

Bard in 1934, while the three men who

headed Bard between these years, 1928–

1944, carried the title of dean. Dr. Butler was

a strong supporter of Bard’s educational

potential, and he worked closely with the

College’s administrators and trustees to

reach this potential, despite the intervening

years of the Depression and WWII.

10. Donald Tewksbury, ca. 1935. In 1934,

Tewksbury was appointed dean of the

College by Columbia’s president, Nicholas

Murray Butler. Tewksbury outlined a progressive

new educational program for the

College that was approved by the board of

trustees. To signal these modern curricular

changes while still honoring its roots, St.

Stephen’s was renamed Bard College. Under

this plan, sometimes called “the inverted

pyramid,” teaching was personalized to the

interests and abilities of the student, the

classics requirements were eased, and the

fine arts were promoted as a division of

study equal to other branches of the curriculum.

The concepts of what have become

moderation and the senior project were also

introduced at this time. Tewksbury resigned

in 1937 as financial pressures mounted.

11. Harold Mestre, ca. 1938. Mestre was a

distinguished biophysicist appointed dean

in January 1938, as the College, facing insolvency,

almost closed its doors. Grass roots

efforts on the part of the students, alumni,

and even the local communities provided

hope in the coming year, but Dr. Mestre

died suddenly on the second day of the fall

semester in 1939. His term was completed

by Bennington President John Leigh, then

on sabbatical. Dr. Leigh provided the trustees with a six-year plan to improve

enrollment, modernize the campus, and

balance the budget, with continued support

from Columbia and the board of trustees.

He nominated his fellow Bennington colleague

Charles Harold Gray for the position

of dean to implement the plan.

12. Charles Harold Gray, ca. 1945. Appointed early in 1940, Charles Harold

Gray was a Rhodes Scholar. Under Gray,

students engaged in issues of campus

governance, reflected seriously on the

purpose of a Bard education, and on the

nature of progressive education in general.

Fraternities and intercollegiate athletics

were phased out during this time. Pearl

Harbor and America’s subsequent entry into

WWII necessitated the hosting of a unit of

the Army Specialized Training Program at

the College, which Dr. Gray oversaw with

care. With the closure of this program, Dean

Gray became President Gray as Bard broke

from Columbia with its decision to accept

women as students, thereby effectively

increasing its enrollment, and permanently

changing the social fabric of the Bard community.

President Gray resigned in the fall

of 1946.

13. Dr. Edward Fuller, ca. 1948. Dr. Fuller

replaced President Gray in October 1946.

Fuller had taught chemistry at Bard since

1935, and, during the war, had worked on

the Manhattan Project based at Columbia.

As president, Fuller oversaw the development

of an innovative integrated introductory

course in the sciences (combining

chemistry and physics), promoted Bard as

a progressive college, and presided over

events such as the international students’

conferences; the 1948 poetry conference;

and student-led projects, including the organization

of the Bard Fire Department and

the founding of the campus radio station,

WXBC. Coeducation and postwar educational

subsidies ensured strong enrollment

for a time, and the College prospered briefly.

Dr. Fuller resigned in February of 1950 to

resume a career in teaching. Photograph by

Elie Shneour ’47. | 14. James H. Case, early 1950s. Case became

president in July 1950, and served in

this capacity for ten years. President Case assumed

the challenge of leading the College

with an energy that bred high expectations,

many of which were met: In 1951, the 825-

acre estate Blithewood was deeded to the

College, ultimately fulfilling the wish of John

Bard, who had lost the property to foreclosure

a half century earlier; in 1952, the

Common Course, now First Year Seminar,

was inaugurated and developed under the

direction of Heinrich Bluecher; in 1957,

President Case opened the College for the

Hungarian Student Program, the humanitarian

impacts of which are still celebrated

today; and in 1959, “The New Dorm”

(renamed Tewksbury Hall) was completed,

further expanding the capacity for student

enrollment. President Case resigned in 1960.

15. Reamer Kline, ca. 1960s. Kline was

President of Bard College from 1960 until

1974. An Episcopal priest, his presidency

was marked by civility, even during this

most turbulent time in the America’s social

history. In 1963, the College purchased

the Ward Manor property, substantially

increasing housing capacity, which in turn

helped to increase enrollment. He increased

faculty salaries, and supported the founding

of the nursery school. He and his wife

Louise opened their home to students

and Bard families for memorable holiday

parties, helping to build a College community.

He hosted a Bard Family Reunion,

bringing Bard descendants back to campus,

and reminding the College of its roots.

Relationships with alumni/ae and the

Episcopal Church were likewise reaffirmed,

and the academic program was strengthened

through hiring which emphasized the

arts. New programs were introduced—including

the Higher Education Opportunity

Program (HEOP), the Independent Studies

Program (ISP), and the Community

Regional Environmental Studies program

(CRES)—and buildings were constructed,

among these Proctor Art Center (now Fisher

Studio Arts), new dormitories called Ravine

Houses, two additions to the library, and

the Kline Commons dining hall. President

Kline supported students during the drug

raids of the late sixties. His final gift to Bard

was the completion of his deeply human

institutional history, Education for the

Common Good: a History of Bard College the

First 100 Years, 1860–1960, without which

the College would be much poorer indeed.

Photograph by Fabian Bachrach.

16. Leon Botstein, ca. late 1970s. The year

2010 marks the happy coincidence of the

150th anniversary of the College and the

35th year it has been served by President

Leon Botstein. In 1975, at the age of 27,

President Botstein accepted the same

challenge faced by most of his predecessors:

to lead a small college with a strong

academic record, but with fragile financial

resources. Like his predecessors, he is an

educational innovator with both the vision

and practicality to put his ideas into effect.

He has been an intuitive administrator and

has taken care to cultivate and work with

talented people both on the board of trustees

and on the faculty and administration of

the College. He has overseen the construction

of bold new buildings, chief among

which are the Olin Humanities building,

the Stevenson Gymnasium, the Stevenson

Library, several dormitories, the Milton and

Sally Avery Arts Center, the Bertelsmann

Campus Center, the Richard B. Fisher Center

for the Performing Arts, and the Gabrielle

H. Reem and Herbert J. Kayden Center for

Science and Computation; and he has also

expanded the Bard name to an array of innovative

graduate programs, early colleges,

and international institutions. President

Botstein also maintains an active conducting

schedule as the principal conductor of

the Bard Conservatory Orchestra and the

American Symphony Orchestra, and pursues

his commitment to teaching, which he

exercises annually in First Year Seminar. |