The following was written by Jeff Katz, former Director of Libraries, at the first launch of the Blücher Archive in 2006:

The lectures contained in this archive are made available to the public for the first time since the 1950s and '60s, when they were first given. The scope of the lectures is grand, encompassing both the history of philosophy and the philosophy of education, the latter often being the subtext for the former. Blücher delivered his lectures without notes or cues of any kind, and for this reason he gave the impression of speaking extemporaneously from the podium. This impression, combined with the fact that he would often follow a line of argument that did not seem to proceed directly out of the main topic of the lecture, suggested that he did not prepare for the lectures in a structured manner, but rather allowed them to form as he spoke. The lectures, when read, convey a sense of structure, however, but a structure that is more akin to Emerson's than Locke's. The conjunctures and links may sometimes be dropped, but only to the effect of bringing the listener into active participation with the lecture, and to the purpose of preparing the listener for a certain kind of inspiration. The lectures are punctuated with beautiful insights, such as the following from the 1954 lecture on Homer:

The eyes of man are sun-like, because art comes and makes them more sun-like. Art is so mighty because it changes our perception of the world. It is almost as mighty as philosophy and not nearly so harmful, because it does not ask anything of us. Art makes no request except one—to be loved—but no other request will a work of art ever make. If we love art and participate in the experience given there then our entire being will be changed, so mighty is this experience and yet so harmless.

The value of the lectures as written material, as nascent essays (and for material that may have been extemporaneous, they do read remarkably like essays), their value must yet be determined by those who will take them up and study them properly. Blücher's wife, Hannah Arendt, was absolutely convinced of the philosophical value of the lectures and of Blücher's thought, which she obviously considered to be highly original and of great importance, as was Alexander Bazelow, the student of Blücher who committed so many hours to painstakingly transcribing hundreds of pages of manuscripts from the reel-to-reel tapes on which the lectures were recorded. Following Blücher's death, it was Arendt's wish that these lectures be published, not because he was her husband, but for their intrinsic value. This website stands as the first step towards fulfilling that goal, after more than a quarter of a century.

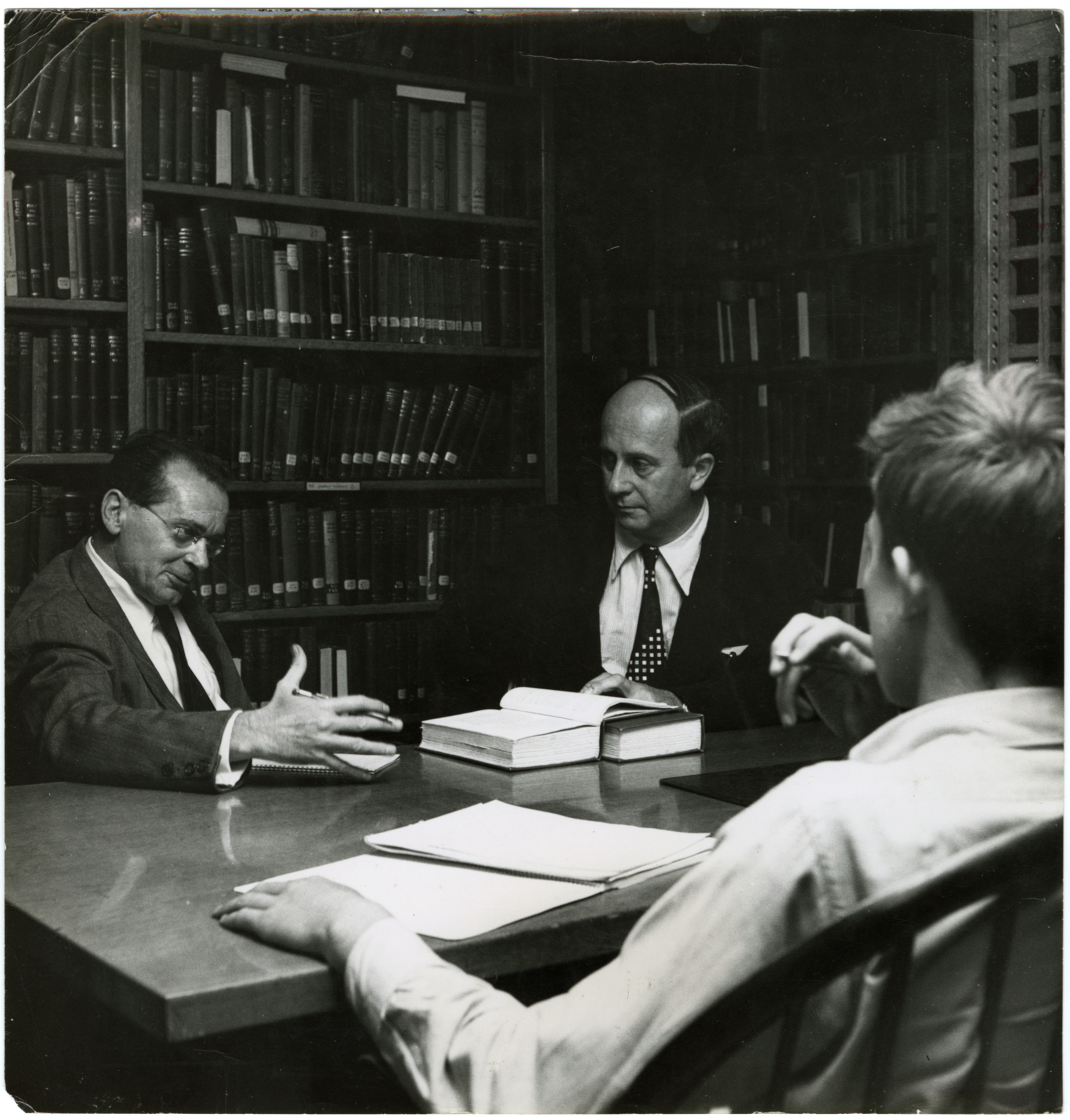

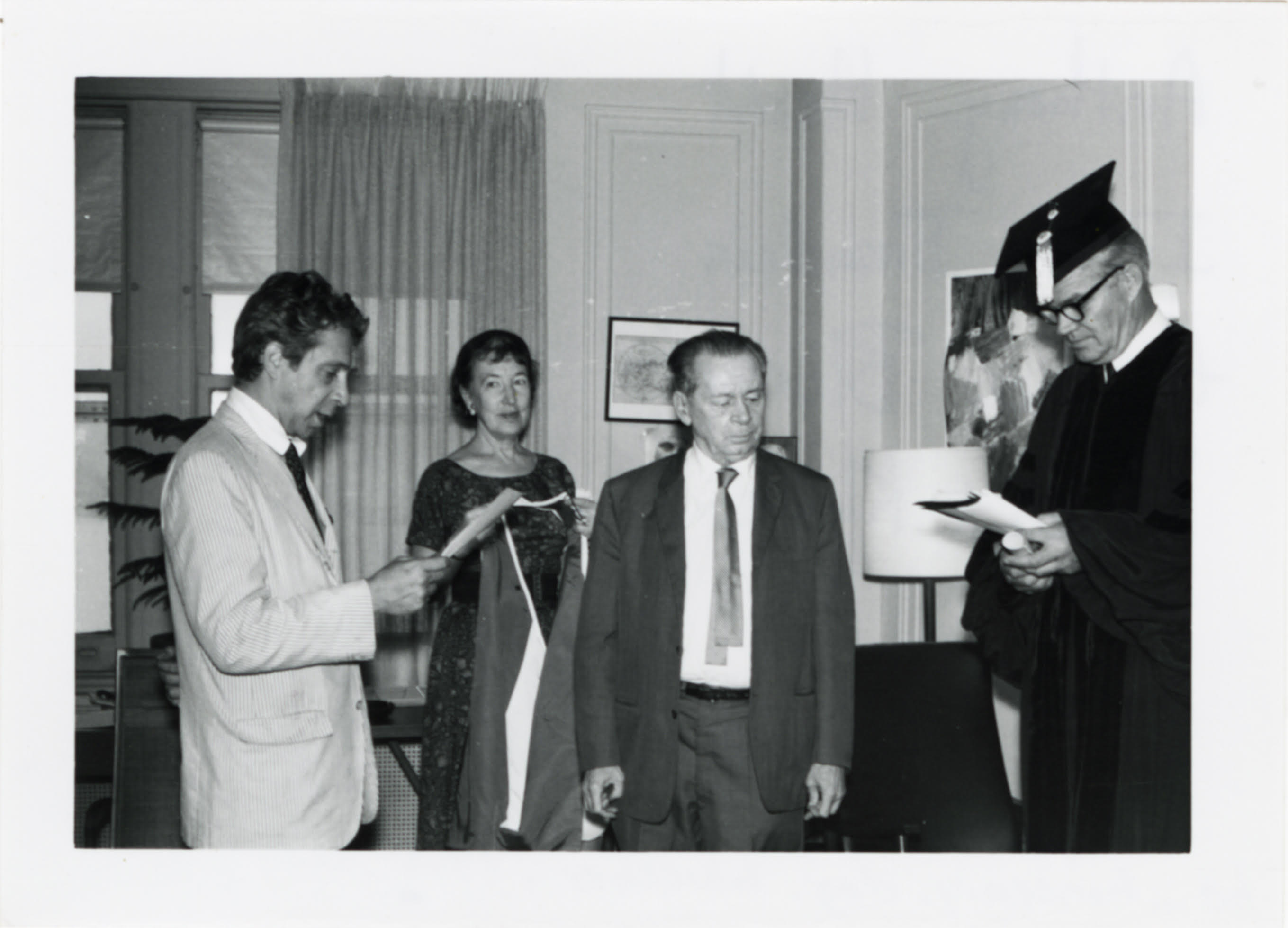

Heinrich Blücher came to Bard College as a visiting professor in 1952. He was not hired by the faculty, but rather directly by James Case, who was at that time President of the College. He developed the Common Course at the college and became its director as well as the primary lecturer for the first-year section of the course, which took as its subject the history of philosophy. His first-year lectures were given in Sottery Hall, which stands just behind the administrative offices in Ludlow. Over the course of the next seventeen years he taught at Bard and at The New School for Social Research (now The New School), in New York City, leaving scores of tapes of his lectures but very little written material. Except for two art reviews, none of Blücher's writing has been published.

Alexander Bazelow ('71) came to Bard ostensibly in order to study with Blücher. Soon after Alex matriculated, however, Blücher retired and Alex switched to a major in the philosophy of science under the direction of Dr. Peter Skiff. Bazelow's attraction to Blücher and his work transcended the end of the student-teacher relationship, and he set out to transcribe Blücher's "Last Lecture" at the college, which he then sent to Blücher with this letter as a preface.

In a letter on June 11, 2002 to Jeffrey Katz at Bard College, Alexander Bazelow wrote:

Over thirty years ago, when I first started working with Heinrich Blücher's transcripts, I came upon a number of photographs of him in his study. One in particular stood out. I set it aside and later, while conversing with Hannah Arendt, showed it to her and asked her to explain its genesis. She explained it as follows: Several months before his death they were visiting friends. While sitting outside, she noticed a particularly reflective expression on his face. Since she had a camera she snapped a picture, put the camera away and then continued whatever conversation had been going on. In the succeeding weeks she forgot about the picture. However not long after his death she came upon the camera and had the film developed. She was struck by the expression in the picture. Most photographs of him make him look somewhat dour, even severe. This one shows an expression of irony, even amusement on his face, a recognition that the mosaic that eventually becomes our life is not necessarily what we would have planned or even expected. She gave me the picture and another of herself. I gave the photo of Hannah Arendt to Lotte Kohler after her death but I kept the one of Heinrich Blücher.

After Blücher's death, Arendt became interested in the work that Alex had begun with the last lecture and asked him if he would transcribe another as a sample. Pleased with his editing, she arranged for him to transcribe the remaining reel-to-reel tapes. (Audio cassette copies of these were subsequently made thanks to Dr. George Rose '63). As Bazelow remembers, "Whenever possible, I used prior material but since no one remembered who these people were no attribution could be made. Generally speaking Hannah Arendt reviewed all of the transcriptions and set aside large blocks of time on her calendar to either work on them alone, or in consultation with me. Where she suggested changes I made them. The material in the archive, though uneven, and in some cases falling short of final publication standards, incorporates all her changes at the time of her death. Comments or notes were usually supplied by me" (Letter to Jeffrey Katz, June 11, 2002). Some ten letters from Arendt to Bazelow concerning the transcriptions exist, dating from April 1972. It is not clear where Alex did most of the transcribing, but he often visited Arendt's apartment in New York City, where he had access to her library as well as Blücher's, which he used in the process of editing and footnoting the lectures. In April 1974, Arendt wrote that MacMillan wanted to do something with the lectures "rather ambitiously," and that one of their editors had paid her a visit and "carried off" the manuscripts that had been completed; she said that they planned a meeting for a "definite proposition" in the fall, and said that she wished Alex to be present. It is not known if this meeting ever occurred. The last letter is dated May 14, 1975. In it Arendt informs Alex that Irma Brandeis has told her that the College still did not have adequate facilities for storing Blücher's tapes and papers, and that she had sent them on to Washington in the care of Mr. Hassan in order to find someone who might be interested in them. These papers finally came to rest at the Smithsonian.

Hannah Arendt died in December 1975, her project of publishing her husband's work unfulfilled. Bazelow had last seen Hannah Arendt on Thanksgiving in 1975 at the home of Hans Jonas. It was Arendt's intention, he reports, "once prior commitments were satisfied, to take my partially edited transcripts and produce a final version herself. What she could not provide materially she more than made up in every imaginable other way. At no time, during my entire involvement with this project, through the frustration with publishers, through her heart attack, whatever, did she suggest stopping, slowing down, or in any way waver in the belief that her late husband's ideas had great merit and deserved to be heard. I think even her closest friends would have been surprised at how much effort she devoted to this, even with flagging health" (Letter to Jeffrey Katz, June 11, 2002).

In a deed of gift she left the tapes of the lectures and the manuscripts to the College. The deed clearly conveys the importance that she placed on these lectures. One condition of the gift is that a committee of eight faculty members be appointed to be caretakers of the materials, the members of which she names and charges with the responsibility to fill any vacancies that should open in the committee. The committee was to oversee the storage of the materials until the Library had adequate facilities for their storage, at which time they were to be transferred there. The manuscripts have been in the Library's possession ever since, stored in Kellogg alongside the Arendt-Blücher library.