In the summer of 2018, a Southern Resident Killer Whale (SRKW) known as J-35 lost her newborn calf shortly after birth. She captured headlines around the world when she proceeded to carry it with her over an unprecedented 17-day, 1000-mile “tour of grief.”

J-35’s calf was just one of three SRKW deaths that summer. By summer’s end, the population had dwindled to 74 whales—a 30-year low. Two years later, it is still only 74 whales. That is a net loss of nine whales from when the SRKWs were listed as Endangered in 2005.

Extinction is not preordained, but at this point it is a very real possibility.

Why are the Southern Residents in Trouble?

SRKWs face a number of threats (PCB contamination, vessel disturbance etc.) but one towers above the rest: food scarcity. SRKWs exclusively eat fish and are salmon specialists with a distinct preference for chinook salmon—the biggest, fattiest, and tastiest salmon on the west coast. An adult SRKW needs to eat around 15 chinook salmon every day. A recovered population would consume upwards of 500,000 chinook annually. And chinook are getting harder to come by.

An estimated 159 of 396 chinook populations the SRKWs evolved to depend upon have been extirpated. The remaining runs have been in a general, if uneven, decline for decades up and down the west coast, but saw an especially steep drop-off after 2014-2016’s marine heatwave. To put it bluntly, there are not enough chinook and the SRKWs are starving to death.

To stave off extinction, year-round chinook numbers need to rebound in a big way and soon. This has landed the orcas squarely in the middle of the most complex, politically fraught issue in the Pacific Northwest: the question of the Lower Snake River (LSR) dams.

The Lower Snake River Dams: To Breach or not to Breach

Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite Dam, collectively known as the LSR dams, are all run-of-the-river hydropower dams operated by the Army Corps of Engineers and built between 1962 and 1975. None of the dams provide any flood control, but Ice Harbor Dam is used for irrigation and all four facilitate barge transport from Lewiston, Idaho. They have all invested heavily in fish passage programs as well as efforts to increase juvenile salmon survival.

Nonetheless, environmental activists, some in orca costumes, hold rallies demanding that the dams be breached to save our salmon. Nothing else will do. Others instead push for increased hatchery production, culls of salmon-eating cormorants, seals and sea lions, and clean-ups of the Puget Sound. For them, breaching the dams is simply a nonstarter. Opinions tend to break along social, political and geographic lines.

For supporters of the LSR dams, people who rely on them for transporting wheat, irrigating vineyards, or direct employment, the targeting of the dams seems arbitrary and misguided: “another example of Seattle-based interests seeking to disrupt our way of life in Central and Eastern Washington.”

For wild fish and orca advocates, Tribal Nations, and people whose livelihood depends on healthy salmon and steelhead runs, breaching the LSR dams is the last best way to quickly recover critical wild salmon populations. They argue that some of the most pristine salmon habitat in the lower forty-eight lies to the southeast of the dams, and removal would allow salmon better access to it.

The debate has gotten to the point where many of the “facts” used by either side aren’t even remotely reconcilable. The dams either have a 96% survival rate or a 17% survival rate. Salmon returns on the Columbia and Snake Rivers are either hitting record highs or they’re cratering. Breaching the dams will increase power bills by 25% while doing nothing to help salmon numbers, or it will increase salmon numbers four-fold and only raise power bills by $1-$3. The cost of breaching the dams will either be $1.3-$2.6 billion or closer to $440 million, and so on.

Both sides scream for policy makers to just “follow the science.” But with such large volumes of conflicting information it can be hard to make sense of what is scientifically sound and what is mostly rhetoric or obfuscation. This in turn makes it difficult to find common ground.

Let’s just look at two key pieces of the dispute: the role of the dams in Washington’s energy grid and the impact of the dams on salmon.

The Lower Snake River Dams and the Energy Grid

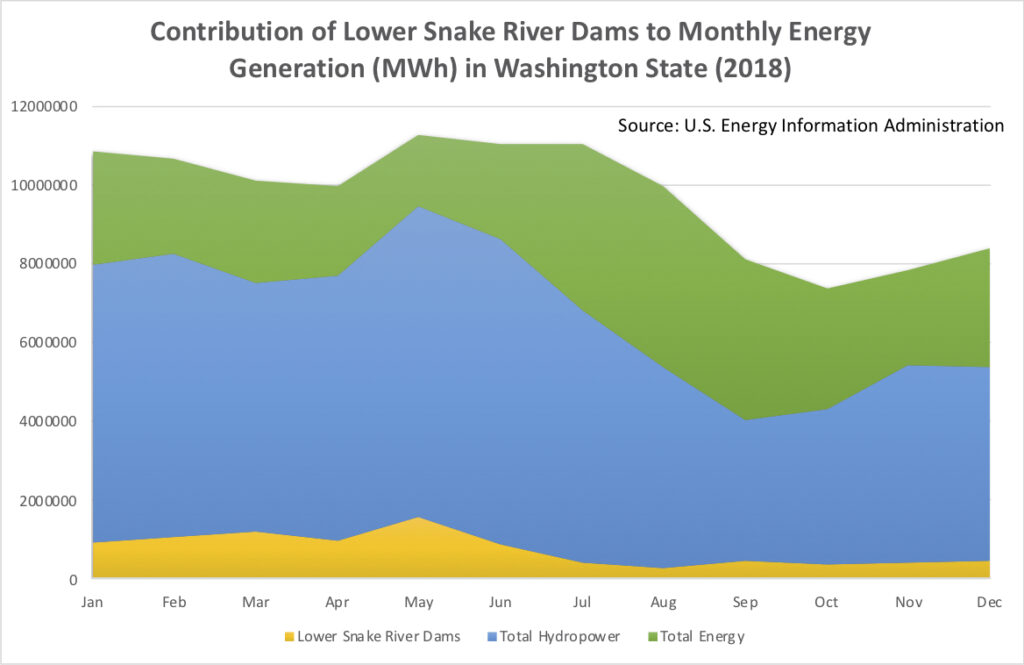

Hydropower looms large in the Pacific Northwest, and in Washington State in particular. Cheap hydroelectricity was a cornerstone of the state’s economic development, and hydropower still accounted for 69% of Washington’s total energy production in 2018. A 2019 Public Policy Survey in neighboring Idaho found that, among dam-breaching opponents, loss of hydropower was the number one concern. There are very real fears in the region that losing the LSRD’s hydropower would drive up electricity rates.

The LSR dams accounted for 9 million Megawatt hours (MWh), or 7.7% of Washington State’s total energy production in 2018, which is not an insignificant figure. That said, Washington State produced 25.6 million MWh more hydroelectric power than it consumed in 2018.

In addition to Washington, Bonneville Power Administration, the federal entity that markets much of the region’s hydroelectricity, has contracts with public utilities in Idaho, Oregon, and Montana. But it is unclear how much of the LSR dams’ energy is used to fulfill those contracts and how much is “surplus.” Dam-breaching proponents assert that the last time LSR dams were used to fulfill contract obligations was in 2009, for just two hours.

Two of the three remaining coal power plants in Washington and Oregon are scheduled to come offline in 2020, and the third is slated to close by 2025. Both states have regulatory commitments to reduce carbon emissions and little public support for new nuclear projects. Anti-breaching Washington Policy Center, expects that this will stress the grid and increase the value of pre-existing hydropower, a “firming” energy resource. They essentially argue that even if the dams are surplus energy now, they won’t be for long.

By their calculations, if the LSR dams were to be breached, 100% of their generating capacity would need to be replaced, possibly with new natural gas plants. Energy Solutions, finding in favor of breaching, calculate that only 87% of the dams’ low-water generation capacity would need to be replaced and could be done so cheaply, without any new gas plants.

Bonneville’s own current projections forecast a 450 MW summer surplus, when the loss of the coal plants is taken into account, which certainly suggests that 100% of the LSR capacity would not in fact be needed.

The Lower Snake River Dams and Spring-Summer Chinook Salmon

The Columbia River was arguably once the greatest salmon river in North America, estimated to have supported combined runs of chinook, coho, sockeye salmon, and steelhead 10-16 million strong. Some estimates put that number closer to 35 million, including chinook runs alone between 4.5-9.2 million. The Snake River is the Columbia’s largest tributary and supplies a significant proportion of the Columbia’s salmon. Today, all four wild Snake River salmonid stocks are endangered. A fifth, wild Snake River coho, is extinct.

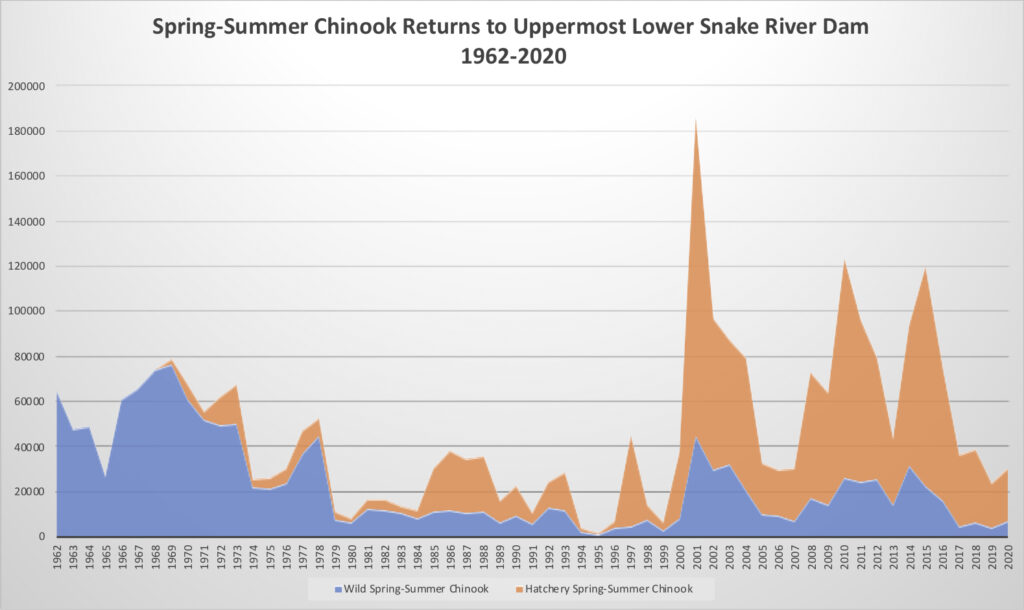

Historically, the Snake River supplied 41% of the Columbia River’s spring-summer chinook. NOAA has identified Snake River spring-summer chinook as one of the top five ‘priority’ stocks for the SRKWs. Since the LSR dams were completed, wild spring-summer chinook returns have dropped considerably.

This decline cannot and should not be completely attributed to the LSR dams. Pacific Decadal Oscillation (e.g. ocean conditions) is a much larger determining factor of adult returns. A regime shift to warmer ocean temperatures from 1977-1998, for instance, lines up almost perfectly with the low returns of the 1980s and 90s.

However, the total number of dams a salmon must pass does appear to increase mortality risk, whatever the reason.

Chinook migrating from the John Day River, for instance, must pass three dams: John Day, The Dalles, and Bonneville. Chinook from the Snake River also pass those three dams, plus five more: McNary, Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite. Despite the fact that every dam has a survival rate of 90% or higher, the average wild spring-summer chinook smolt-to-adult-return ratio (SAR) for the Snake River is 0.92%, while the SAR for wild spring-summer chinook in the John Day River, ostensibly facing the same ocean conditions, is 4.21%. A SAR of 1-2% is necessary for stock maintenance, while a SAR of 4-6% is considered the minimum for stock rebuilding.

It’s important to note that the LSR dams are not inherently worse for salmon than the other 250+ dams in the Columbia River basin, as is sometimes implied by their “salmon-killing” epithet. It is rather the cumulative effect of multiple dam passages that appears to disadvantage Snake River salmon.

To Save the Orcas and the Salmon, We Need to Start With Some Common Ground

The state’s Stakeholder Engagement report highlighted the deep resentment felt by many in Eastern Washington towards “the coast,” especially when it came to acknowledging the sacrifices people were being asked to make. It does not mean that removal of the LSR dams is not in fact the quickest way to restore the wild salmon populations in the Snake and Columbia Rivers, and possibly the SRKWs. But it is also the solution that affects the lives of people in the Puget Sound the least, and we could do more to recognize that. Puget Sound residents can and should take action a little closer to home. Waterfront property owners could take out their bulkheads, for one. The orcas need all the salmon they can get.

Getting past ‘agreeing to disagree’ requires mutually agreed upon facts, up-to-date data, respect for and understanding of different perspectives, and probably compromise. Luckily, the Stakeholder Engagement report also found that everyone on both sides is so exhausted by 35 years of constant litigation that we just might start to get somewhere.