On a crisp fall day some several years ago, I left my house in rural Connecticut for a contemplative walk in the woods. My restless teenage legs were matched by my curiosity about the world around me. Down a wooded path with no houses in sight, I stopped to rest along a stone wall that marked the end of one trail and the start of another. “Who would build a wall way out here?” I naively wondered. “Why go through the effort?”

Perhaps you, too, have wondered why a network of stone walls divides seemingly vacant forests across the Northeast. The answer is that these common yet quintessential features of New England forests are remnants of an agricultural legacy nearly four centuries old.

New England’s Land-Use Past

Once home to an extensive wilderness of old growth forests, vast swaths of New England were cleared for agriculture and timber products, beginning with European settlement in the 17th century and continuing into 19th century. Farmers constantly  turned up stones and cobbles—remnants of New England’s glacial past—which they then discarded to the edges of their fields, forming the stone walls we still see today.

turned up stones and cobbles—remnants of New England’s glacial past—which they then discarded to the edges of their fields, forming the stone walls we still see today.

New England’s natural history is therefore one of transition from mature forest to early-American agriculture, then through species succession to the forest we see today.

Land Protection in New England

Efforts to safeguard New England’s iconic landscape—both its forest and agricultural legacies—are also in a state of transition. Especially in the Northeast, today’s land conservation landscape in America looks quite different from the time of prominent figures like John James Audubon, John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, and Aldo Leopold. Compared to the National Park and National Wildlife Refuge system, protecting biodiversity and special places in the Northeast faces the challenge of working within a patchwork of privately held and subdivided land.

In the early 1980s, Congress finalized a set of incentives that allowed private landowners to donate land-use rights (e.g. development or subdividing), and the land trust movement was given new life. Since the first land trust was established in Massachusetts in 1891, the land trust movement has grown to over 1300 active land trusts, 388 of which are in New England, actively protecting land from development at the local level. Collectively New England’s land trusts have protected over 8.5 million acres across six states. The pace of land conservation has been remarkable in the past few decades thanks to the work of many hundreds of dedicated men and women.

However, the work is far from over. The competition for open space in the Northeast is high, as is the risk of climate change impacts to the region. Funding constraints and the ever-present drive to make conserved land relevant and accessible to more people have many conservationists asking, “How can we do more with what we have?”

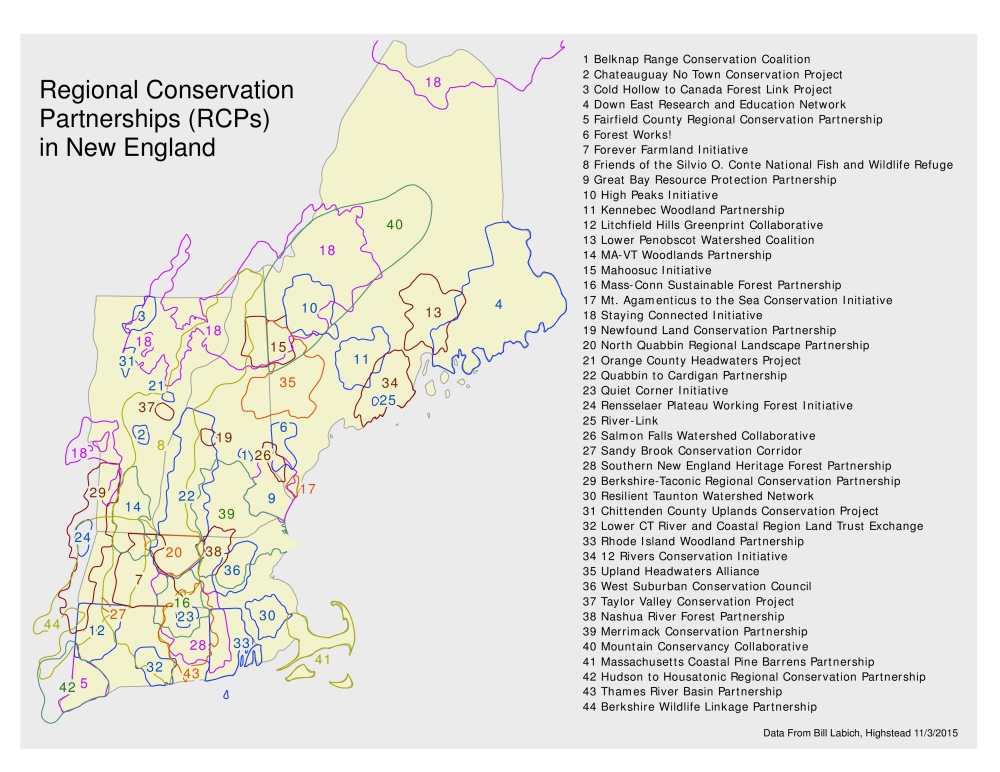

As an aspiring conservationist, I’ve set out to generate some answers to this question. Speaking with Spencer Meyer, Senior Conservationist with Highstead, it seems that many local area land trusts have found that part of the answer lies in creating partnerships with fellow conservation groups and non-traditional partners.

Continued in Part II – Spanning Boundaries