The Wallkill River begins in northern New Jersey, at Lake Mohawk. Flowing north ninety miles, it joins the Hudson River at Kingston. The Wallkill flows through abandoned mines, a national wildlife refuge, and some of the richest farmland in the country. It still has dams strung like beads along it’s northern reaches. Relics of a long gone industrial age, a few remain useful as hydropower stations. Otters play in the waters and herons fly at dusk, their silhouettes ghosting across the sunset.

And last year it turned bright green. And the year before that. Come August, we expect it to be green again, choked with toxic cyanobacteria as miles of the river succumb to another Harmful Algal Bloom—an HAB. Approximately thirty miles of the river (from Montgomery to Rifton) will be contaminated, dragging on for three months, from August through October.

Monitoring the river, and the proliferation of HABs, is the Wallkill River Watershed Alliance. One goal of the Alliance is reducing pollutants to below acceptable thresholds, including nutrient levels. But what motivates the Alliance is the simpler, more visceral goal of a river we can swim in, enjoy paddling kayaks and canoes in, and safely eat the fish out of. For the Alliance, a Harmful Algal Bloom is a symptom of a larger sickness.

Why Does Toxic Algae Bloom?

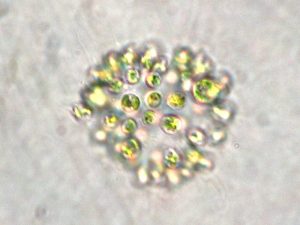

Algae, of course, is an important part of aquatic food webs and ecosystems, and is normally harmless. However, under certain conditions, algae can reproduce very quickly, causing a bloom. If these blooms are generated by certain toxin-producing algae species, they are classified as a Harmful Algae Bloom.

Caused by a variety of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, HABs are largely the product of the organisms Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, and Microcystis, known colloquially among scientists as “Annie, Fannie, and Mike.” All three produce toxins that contribute to the symptoms listed above, and can lead to serious damage to the central nervous system and the liver. All three were found in the Wallkill River last year, especially Microcystis.

All three are also among the oldest organisms on Earth, estimated at 3 billion years old, and—one assumes—have been in the Wallkill since soon after the glacial retreat carved the river’s valley.

So if Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, and Microcystis have been in the Wallkill since the beginning, why are they only blooming now?

There are three conditions that likely to cause a Harmful Algae Bloom:

- The water has to be sluggish, or have low flow. For this reason, most HABs are reported in lakes. HABs in rivers are still rare, and the Wallkill is one of the few to have reported a HAB in New York State. However, given the drought conditions in recent years, combined with the fact that the section of the river plagued by a HAB contains a series of dams, it is possible that in the late summer and early fall, the northern Wallkill acts more like a series of lakes and less like a river, at least from the point of view of the cyanobacteria.

- The water has to be warm enough—higher temperatures increase the chances of a HAB. Given that every year sets new global temperature records, it is becoming more common for waterbodies to cross the temperature thresholds under which HABs flourish.

- The must be enough nutrients (mainly nitrogen and phosphorus) in the water to feed a bloom. Waterbodies being polluted by nutrients (from agricultural runoff, municipal sewer systems, and/or leaking septic tanks) are therefore priming the pump for a HAB.

The Wallkill River Watershed Alliance Responds

When the algae bloomed last August, the Alliance’s Science Working Group and our allies at Riverkeeper quickly responded. We had already been collecting samples to test for nutrient levels at the Wallkill’s tributaries that summer. Now we added sampling in Montgomery, New Paltz, and Rifton three times a week for the duration of the bloom. We sent some samples to SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) to be tested for toxin levels.

Alliance scientists (as well as SUNY ESF) confirmed the presence of Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, and Microcystis. SUNY ESF also confirmed multiple samples as toxic: one sample taken at Sojourner Truth Park in New Paltz was found have eighty-eight times the safe toxin levels established by the NYS DEC.

What Happens When the Blooms Come Back?

All indications suggest we are likely to see another bloom in the Wallkill this summer. Temperatures are expected to increase, and along with higher temperatures come increased droughts. Nitrogen and phosphorus continue to constantly leach into the river. The question is less whether a bloom is likely than how big the bloom will be and how long it will last.

In late winter, Dr. Robyn Smyth of Bard College’s Center for Environmental Policy contacted the Wallkill River Watershed Alliance was contacted about a joint project for rapid response monitoring to a developing Harmful Algae Bloom. The project would sample for toxins wherever a bloom may develop on the river, allowing for more accurate warnings to the public as well as valuable data collection.

In addition to developing a standard sampling regime, the project would test the expected HAB for airborne toxins, which can transport microbes far from the origin of the bloom, and lead to both respiratory issues and chronic health problems.

Join the Fight to Save the Wallkill River

Because it’s so unusual for a river to host an HAB, the Wallkill can be seen as a canary in a coal mine. The increase in temperature and droughts brought on by climate change is expected to make harmful algae blooms both more frequent and more severe. But we can work to prevent them, or at least lessen their impact:

- Inspect and maintain your septic system. Nutrients making their way into the water from

A riparian buffer. Photo from Wikimedia Commons. leaking septic systems contributes to the pollution that causes HABs. Please have your septic system inspected regularly.

- Advocate for upgrades to municipal sewer systems. Local governments can search out grant funding (such as the Community Development Block Grant program) and rural communities can get low-interest loans from agencies such as USDA. Upgrades to aging sewer lines and under-capacity wastewater treatment plants are potentially a large source of nutrient contamination to waterways.

- Plant riparian buffers. Planting trees and not mowing along stream banks can allow those plants to act as a filter, absorbing the nitrogen and phosphorus instead of allowing itto wash into the river. These buffers are especially important for farms.

- Develop green infrastructure. Many technologies exist to slow, filter, and/or clean urban stormwater runoff, which is choked with pollutants from all the streets and buildings it washes. Technologies like rain barrels, rain gardens, and even constructed wetlands can be used to mitigate some of the damaging effects of stormwater.

The Wallkill is a beautiful, but troubled river. The recent appearance of the first harmful algal blooms coincided with the founding of a community organization capable of monitoring and measuring it. While climate change will undoubtedly bring more HABs in coming years, we can protect the river (and ourselves) by reducing nutrient pollution. The less we poison our river, the less it will poison us.