Cairns is a small city that sits on the east coast of northern Queensland, Australia – head a bit further east (I recommend you take a boat) and you’re greeted by the wonders of the Great Barrier Reef. Drive north, and you’ll find yourself among the Daintree, the oldest rainforest in the world.

The city’s proximity to these magnificent places gave the region its famous slogan ‘where the rainforest meets the reef.’

When the Bard CEP faculty told me, “Intern wherever you like, so long as it’s focused on environmental policy,” my mind went straight to Cairns (my heart had never returned from an initial visit). It seemed obvious that a place teeming with ecological activity would be a policy hotspot. Luckily, my determined searches led me to the Cairns and Far North Environment Centre (CAFNEC), where I am currently interning.

CAFNEC in a shell

Where there is wilderness, there is history.

Learning the timeline of Australian conservation efforts has been one of my personal goals at CAFNEC, in attempt to better my understanding of the dynamics within the community. Much like the US environmental movement, concern over the protection of Australia’s natural history grew in the 1970s as conservation groups and community members joined forces to end logging in the Daintree – some held off bulldozers on the ground, others from the treetops.

The idea CAFNEC grew out of conservationists’ recognition that a non-profit organization was required to hold government officials and interest groups accountable, understanding that some groups could be paid off by developers.

In 1981, CAFNECs became the first high-profile organization to serve as a primary contact point for those tackling environmental issues spanning over 600 miles along the Queensland coast.

Public meetings that educated local stakeholders led CAFNEC and other key NGOs to successfully block further development of the Daintree and obtain a World Heritage Listing for the Wet Tropics in 1988.

CAFNEC’s presence in the community increases interaction between the scientific world and concerned citizens, raising awareness and building networks of conservation organizations, cultural groups, and natural resource stakeholders.

Collaboration with a variety of groups and volunteers from the community drives CAFNECs success, making it a celebrated environmental organization that continually aims to educate and inform the public on environmental issues of state and national importance, no matter the obstacle.

Built on the idea that local advocacy is a powerful political force, community members continue to be the heartbeat of CAFNEC.

What’s on at CAFNEC?

To keep community members aware and engaged, CAFNEC provides heaps (excuse me while I pepper in some Aussie lingo) of opportunities for education and mobilization. Some ongoing projects include Drain Stenciling, Boomerang Bags, and MangroveWatch.

- Drain Stenciling is a hands-on educational project that engages children of all ages to play a role in informing their community on how to improve marine water quality. CAFNEC organizes school groups and families to stencil the message “This drains to the Great Barrier Reef”beside drains throughout the city. The combination of a powerful message, bright colors, and some fantastic sea creature stencils makes a little sidewalk art to go a long way.

- Boomerang Bags is a community group that sews donated fabric into reusable bags, making alternative options available to the broader community. In addition to the sewing group, volunteers run events at city centers to discuss options for cutting single plastic use and hand out reusable grocery and produce bags to anyone interested in making a transition to more sustainable alternatives.

- MangroveWatch is a citizen science program for monitoring the health of mangroves and saltmarshes in tidal wetlands. Trained community members and organizations collect geotagged video data of shoreline that’s later analyzed by researchers at the Center for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystems Research (TropWater).

My roles at CAFNEC

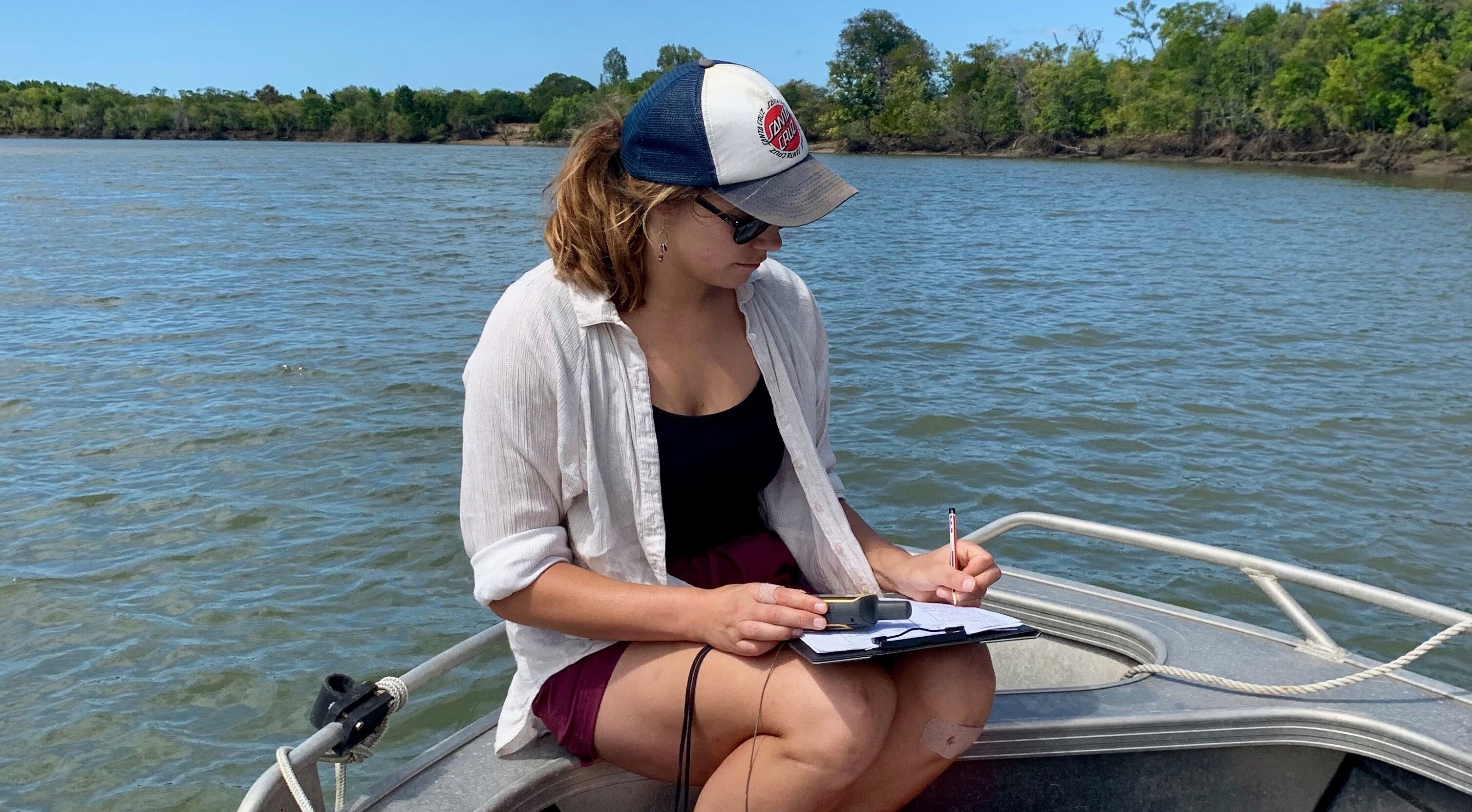

I’ve dipped my toes in each of the projects mentioned above; however, I quickly became consumed by MangroveWatch. Sure, spending full days on a boat identifying mangrove species easily tops sitting at a desk answering emails, but it is so much more than that.

MangroveWatch is an opportunity available to anyone with access to a boat, and in northern Queensland that’s just about every other household.

The goal is to compile as much video footage, and as many notes, verbal observations, and photos as possible to maintain a record of changes over the years. Local fisherfolk, for instance, are taped discussing their observations of more sediment build-up, leading to less water flow and more undercutting below root systems. These conversations demonstrate that concerns among the local community align with those in the scientific community. MangroveWatch aims to bridge that knowledge and raise awareness.

Over the past couple of months, I’ve been mapping the MangroveWatch tracts from the past two years and learning the essentials for proper data collection. We have a few more tracts to complete before the end of 2019.

Once completed, all the data will be sent to TropWater for analysis and compared with data collected 12 years ago.

While offshore monitoring gives researchers a closer look than the alternative aerial footage, it still has some drawbacks. It’s difficult to get to know a plant without getting up close and personal, so those without a background in mangrove ecology (like myself) have a hard time identifying species from a distance.

The Jack Barnes Mangrove Boardwalk is an access point for anyone to get an educational up-close experience with mangrove species. Unfortunately, the boardwalk is currently closed due to lack of maintenance and upkeep.

In the upcoming months, my roles will include continuing community outreach efforts to get locals trained for mangrove and saltmarsh data collection and building a campaign to get the Cairns Regional Council to reopen the Jack Barnes Boardwalk for public access.

How good* is interning?

Sometimes I still have to pinch myself to remember this is real life. I am so unspeakably grateful to Bard CEP for making the internship experience a key component of the program. After my first year at Bard CEP, long days on a boat in the sun feel easy (jokes aside, the hardest part of those days is not getting in the water because there are crocs and they will eat you).

I think it goes without saying, but that intensive first-year of coursework certainly pays off.

*’How good’ is a rhetorical question in Australia.

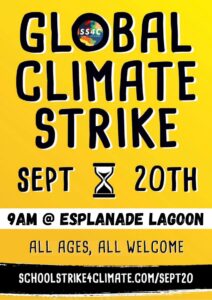

Sidenote: Another small role of mine with CAFNEC has included working with James Cook University and Cairns high school students on the upcoming #GlobalClimateStrike. I can’t take any responsibility for the organizing behind the scenes because all I do is show up and marvel in their determination and leadership skills. So, wherever you are in the world, get out there on September 20th and show your solidarity with the brilliant students demanding climate action!