Big Sky Country. What runs through your mind when you read those three words? A never-ending canopy of blue skies, perhaps? The wide open spaces of ranch land, home to cowboys and cattle? Or crystal-clear rivers teeming with trout, meandering through green meadows bordered by snow-capped peaks?

For me, and for those who call Montana home, it is all of these things. But it is also a place of abandoned and active asbestos, sapphire, and gold mines. It is a place that’s advancing national and global development through the extraction and export of fossil fuels – solid, liquid, and gas. It is a place of limited natural resources stressed by an increasing population and a changing climate.

Montana’s environmental and ecological challenges are varied and complex. A multitude of stakeholders, from local community members to federal government officials, hold a spectrum of opinions regarding the use and protection of the state’s resources.

It is no wonder that a state so diverse is home to hundreds of non-profit environmental organizations, each with their own vision for a better Montana.

But what makes these organizations successful? One answer: Individuals committed to a vision that educates others and inspires them to take action toward a cause. These individuals are leaders, and they are the reason why citizens of Montana call it The Last Best Place.

But what makes these visionaries leaders? What are the skills necessary for effective leadership?

Webster’s rather poorly defines leadership as “the power or ability to lead others.” Business-related blogs and websites offer multiple answers, some stating outright that leadership cannot be taught. Instead, leadership is akin to a recipe with the necessary skills as ingredients. A dash of this and a pinch of that and, bam, a leader is born. Tweaking the ingredients often improves the metaphorical mold. But a missing ingredient almost always spells disaster.

To find out what these ingredients are, I spent some time earlier this month with directors from two distinctly different environmental organizations located in Bozeman, Montana, a growing college town nestled at the foot of the Gallatin Mountains and a gateway city to Yellowstone National Park.

Citizen Science to the Extreme

Gregg Treinish is Founder and Executive Director of Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation (ASC), a non-profit organization enabling informed conservation decisions by supplying partners with difficult to obtain data, grassroots support, and outreach by leveraging the unique skills of the adventure community. Gregg, a biologist and accomplished outdoor adventurer, founded ASC in 2011 after identifying a gap between the scientific community’s quest for scientific data and its difficulty in physically accessing it.

In four short years, his idea has grown from a website and a network of top outdoor athletes to a half-million dollar a year organization with over a dozen conservation partnerships focused on data collection over all seven continents and five oceans. These projects include high-altitude snow and ice studies, analyses of micro-plastics in salt and fresh water, and wildlife and land conservation in Montana’s prairieland.

Protecting our land for Present and Future Generations

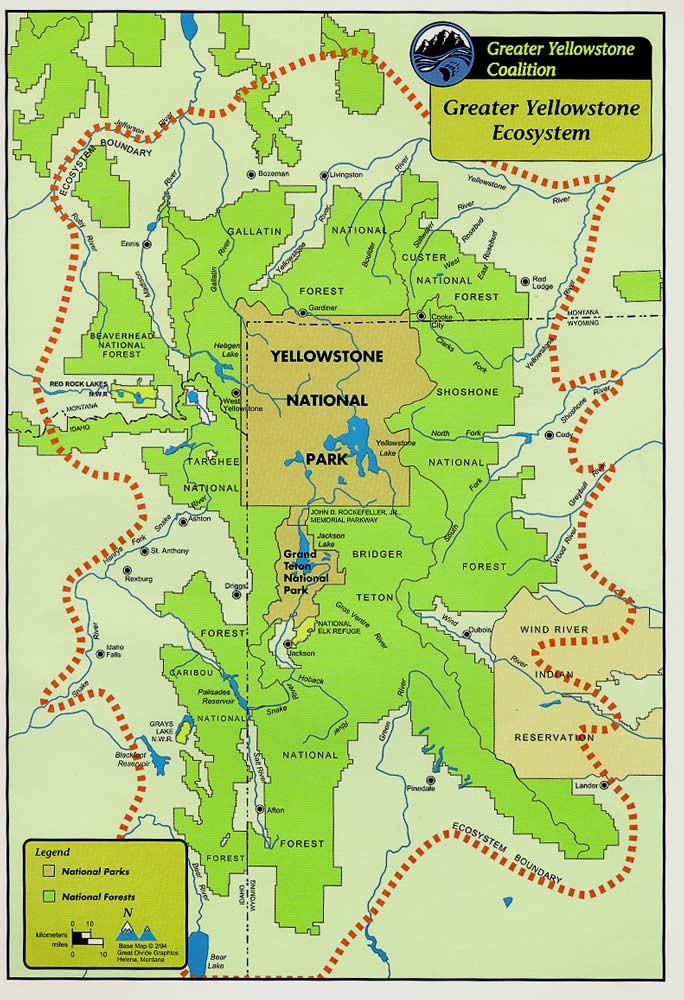

Scott Christensen is the Director of Conservation at the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, an organization dedicated to protecting and preserving the lands, water, and wildlife of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem for over 30 years. He is a longtime outdoor enthusiast, spending his free time riding whitewater rapids, rock climbing, and fishing.

Scott oversees the entire conversation team, a diverse group of employees working in three states. His professional experience includes efforts to restore degraded rivers and streams, protect public and private lands, and help revive the native cutthroat trout population in Yellowstone Lake, a keystone species crucial to the larger ecosystem.

What skills make an effective leader?

ASC and GYC are very different organizations. But their respective leaders are committed to their organizations’ missions and to their own individual goals. In fact, these are two leaders with similar skills in their leadership toolkits and similar ideas on what makes a great leader.

Network. Network. Network.

Gregg may have begun his organization with a simple idea and passion for science and adventure, but he knew it would take more than that to get this idea off the ground. He needed help from those in the outdoor and scientific communities. “I knew right away that I needed a board of directors to help shape my vision,” states Gregg. “I reached out to Conrad Anker to join the board, as well as other top scientists and athletes. I wanted to include the best people not only for their inspiration, but because they are ambassadors of their fields and, in turn, would become ambassadors for this organization.”

Today, the ASC board of directors and advisory council includes multiple award-winning business leaders, educators, scientists, film-makers, writers, and photographers.

Developing and Maintaining Relationships.

Similarly, Scott notes that for a larger organization, managing relationships is essential. “You must always be aware of stakeholder relationships. But you must also know how these relationships change from issue to issue,” says Scott. “In order to keep these relationships in perspective, I think of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem as a town. Everyone might have their own interests, but everyone must work together to be successful. Therefore communication and trust is key. Stakeholders may not agree on every topic, but they will agree 80% of the time. So you are looking for bright spots and working from there.”

Recently, GYC has worked with private land owners and the federal government to expand bison grazing outside of Yellowstone National Park by 400,000 acres in Wyoming and 240,000 acres in Montana. GYC has also worked to improve water conditions through its Wild and Scenic Rivers campaign and has helped in halting a proposal for a gold mine in Paradise Valley.

Goals are essential, but flexibility is key.

Leaders must also remain focused on the long-term while adjusting near-term plans. An overarching idea without short-term planning often leads to disaster. The opposite – multiple small-scale efforts without a larger goal – can also bring about failure.

Scott notes that long-term visions balanced with benchmarks help you understand the capacity of your organization. He states, “A clear vision keeps you focused and allows you to ask questions and think strategically. In essence, you are asking yourself, ‘What do we need to get to where we are going?’” Understanding how short- and long-term goals fit together allows for a constant evaluation process.

Gregg likens this to the skills he learned as an adventurer, planning out a trip step by step and looking forward to the outcome. “You are always striving for balance,” notes Gregg. “There is a combination of optimism and creativity in planning, knowing that everything will work out.” Gregg sums this up best by saying, “There are never any obstacles, only challenges and opportunities.” Gregg also offers what is perhaps the most resonant analogy between the NGO and outdoor adventure: “To quit is to die.”

Never stop learning.

One key trait of any good leader is the ability to recognize your own strengths and weaknesses. A great leader, however, will take the extra step to improve upon their strengths and develop the skills necessary to reduce weakness. For Scott and Gregg, this means surrounding yourself with mentors and coaches. As Scott states, “You need to create opportunities to work with mentors. Be deliberate in finding a mentor and straightforward in your desire to improve.”

Mentors and coaches will not only help you improve but will help you navigate failures. As Gregg notes, “Failure must be a part of your leadership toolkit. It helps you learn and grow as a leader.”

Gregg also points out that it helps to surround yourself with a team diverse in their own skills. “It keeps you motivated to learn and do more.”

There really is no one definition of leadership.

Overall, great leaders are those who can identify a need and motivate others to not only also see that need, but motivate them toward providing a solution. They look for bright spots when faced with resistant stakeholders and do not hesitate to turn to friends, colleagues, and community for help and advice.

Moreover, leaders welcome the challenge, do not flinch in the face of failure, and see obstacles as opportunities to improve.

Knowing this, it is no wonder that ASC has grown from an idea and a website to an internationally recognized NGO in four short years. It is also why the Greater Yellowstone Coalition continues to do so much great work and continues to grow as an organization after 30 years of dedicated work in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Gregg Treinish and Scott Christensen are the embodiment of great leaders.