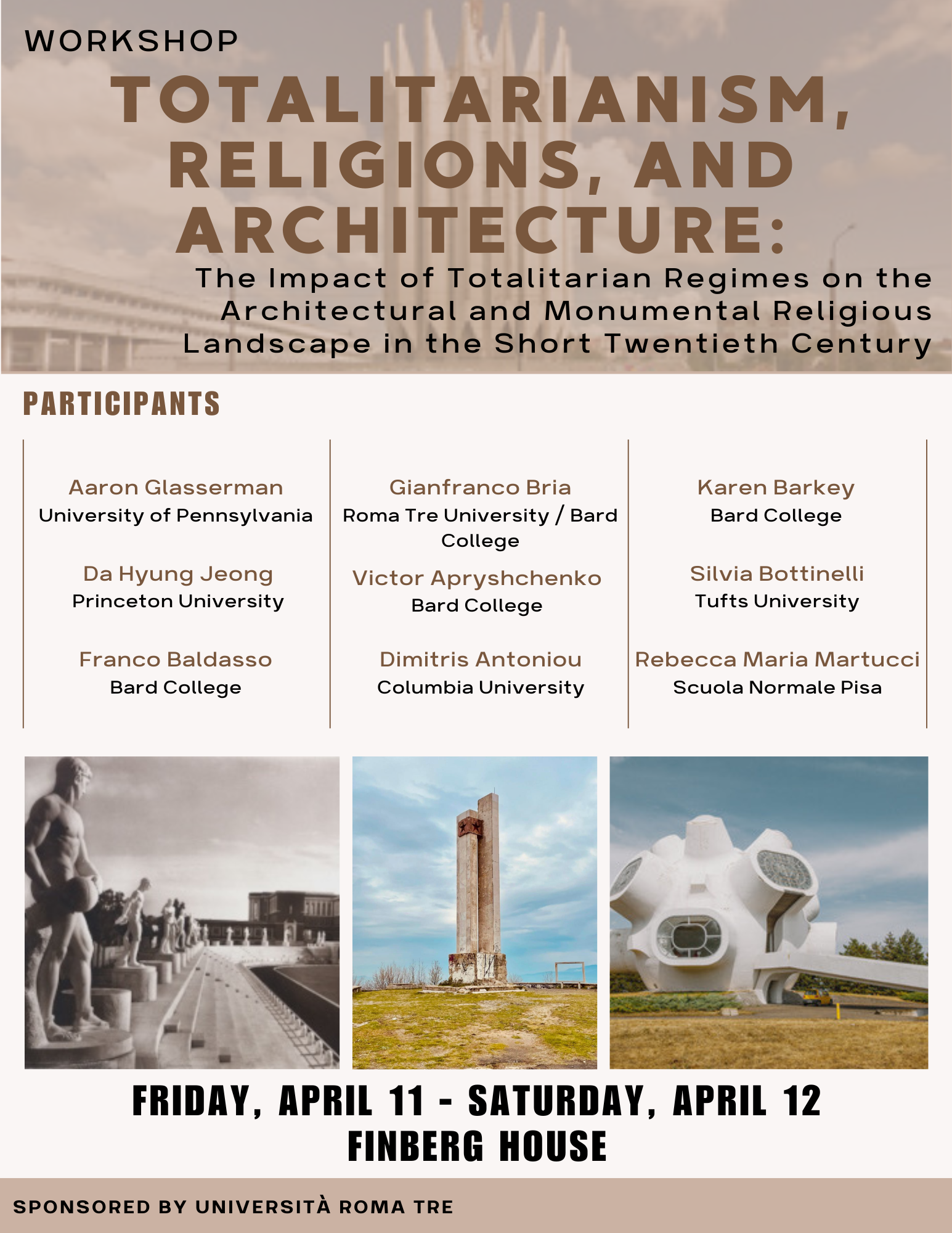

Totalitarianism, Religions, and Architecture: The Impact of Totalitarian Regimes on the Architectural and Monumental Religious Landscape in the Short Twentieth Century

Friday, April 11, 2025 – Saturday, April 12, 2025

Finberg House

The “short 20th century” was marked by totalitarian regimes, which profoundly impacted the society they governed. Such regimes comprehensively and tremendously planned to mobilize masses and gain their consensus through direct control of the lives of individuals and by enforcing collective rituals, myths, and rhetoric. Militarized corporality, high–impact aesthetic symbolism, political liturgy and leaders’ worship are just some of the aspects that typified these regimes’ actions in shaping public space. This led authors, like Emilio Gentile and Robert Mallett, to use the term “political religion” to indicate the evocative reach of totalitarian regimes' narratives and symbols to create a cultural memory by which masses can envision themselves as a single, cohesive social body. Building cultural memory involved shaping a material and visual culture that evoked the autopoietic national myths and the palingenetic past inspired by the regimes, as in the case of the Roman Empire for the Italian Fascism. In such a way, Fascist, Nazi and Communist regimes actively used architecture as a tool of creating influence in rational and emotional perspective. They shaped the urban and rural architectural landscape according to their conception of history (past, present, and future) and the people as a nation. This included at times the enshrinement of religious architectural and monumental heritage. These totalitarian regimes molded their relationship with religious institutions and traditions since their oriented conception of religion. This was discernible, and an extremization of post–Westphalian understanding about religion was based on a dialectical relationship between political power and religious institutions in which the latter are essentially subjugated to the former. However, this did not preclude regimes, such as the fascist one, from establishing agreements and collaborations with religious institutions, nor did it prevent their state secularism from mimetically and selectively embed some religious practices or symbols. In the case of communist and socialist–relative regimes, it could happen that state institutions subjugated religious ones in what we might call the “domestication of religion” which could involve blatant anti–religious conflict, as in the instance of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, or even the incorporation of national worship and state ideology into religious organizations. Indeed, it also included the shaping of the architectural religious landscape, which could be subdued to state purpose or even targeted by the anti–religious campaigns as in Albania’s in 1967 when churches and mosques were closed, destroyed or converted to civilian uses. Yet in the case of communist–inspired regimes as much as fascist ones, it would be inaccurate to believe that state institutions were able to totally erase the religious monumental and architectural landscape: both religious authorities and faithful were able to develop practices of negotiation and resistance through re–using and preserving religious spaces. Specific sacred locations were occasionally used to elaborate the cultural memory of religious communities, as happened in Soviet Central Asia. This workshop aims to investigate, according to various epistemological perspectives (historical, anthropological, architectural, archaeological) and through different methodological approaches how totalitarian regimes in the short 20th century shaped the religious monumental and architectural landscape.

For more information, call 845-758-7662, or e-mail [email protected].

Location: Finberg House